They may be only around 1 cm long – but with thousands of relatives they can devastate a vineyard in one night. It is an on-going problem, and while research into pastoral control of the grass grubs has been happening, very little has been undertaken in vineyards.

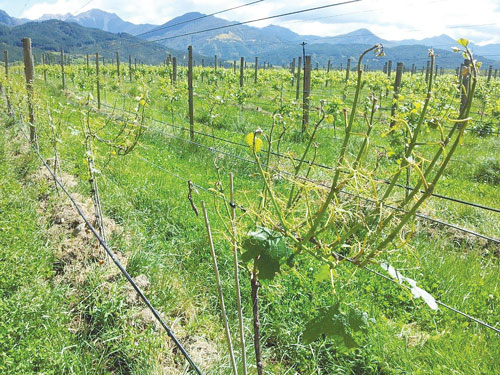

There is a subtle difference of course. Pastoral damage is caused by the grass grub itself – or the larvae of the beetle. However in vineyards, the major damage is caused by the adult beetle. (That being said the larvae can cause problems to the roots of vines as well). During a short time frame of three to four weeks over November and early December, the adult beetles appear in their thousands, landing on the newly burst leaves and buds.

Last year Lincoln Unviersity PhD student Mauricio Gonzalez Chang undertook a research project to try and understand the behavior of the beetle in vineyards and potential ways of diminishing its impact.

Working with Kono Beverages in the Awatere Valley (Marlborough) Chang established infra red light cameras among the vines to gain a clearer picture of what the beetles were doing and when.

Those cameras showed that the beetles began flying 30 minutes after sunset. (In this case it was between 8.15pm and 9pm). Initially they hovered over the grass near the vines and then descended on the vines themselves.

"We still don't know if the females fly first and release sex chemicals (pheromones) which attract the males," he said.

But what he did notice was that each flight began outside the vines themselves, with the beetles coming from the headlands, wild grass and sometimes neighbouring vineyards.

"They then accumulate on the young vine plant tissue where they mate. Mating is over a two-hour period and then they feed for around three hours. They then drop to the ground between 11pm and 1am."

That explains why you don't know you have a problem until it's too late – given the beetles are never seen in daylight hours.

Chang said the beetles began appearing on October 27 and were present until December 2.

"There was a huge peak on November 14 and we are still trying to understand why there were so many ups and downs in numbers during the period."

The vines nearest the edge of the vineyard were the ones that were initially most affected, understandably given they are closer to the source of the beetles. However over time, there was an increase in the damage to vines in from the edge.

"That might indicate that after the defoliation (at the edge) the beetles were moving inside the vineyard looking for more food."

Winter sampling of larvae also showed that there were fewer larvae under the vines and interrow, the further into the vineyard you went.

But there were also more larvae immediately under the vines at the edge than there were in the interrow.

But there were also more larvae immediately under the vines at the edge than there were in the interrow.

"This is explained by the adults dropping off the vine, straight down, which is where they lay their eggs. Only some land in the inter row."

Which led Chang to research whether there was a product that could prevent the adults damaging the vines and laying their eggs underneath. The product used was mussel shells. Thick layers of the shells were laid directly under some of the vines, to see if this had an impact.

"We had a very unexpected result," he said. "One night I went into the vineyard and counted the beetles and I saw the plants that had shells below them had 69 percent fewer adults on them than were on the vines without shells underneath."

At this stage he is unsure why – but plans further research to find out. He also said he needs to research whether there is any difference between using old mussel shells compared with new

New shells have more of a fishy smell, which may be a deterrent to the beetle.

"We also need to see if this approach has some effect on the vines. Does it add calcium and will it affect soil pH which could affect the wine?"

Another experiment undertaken last year was the use of feeding deterrents – diatomaceous earth (DE) and kaolin based dust (clay).

"We used diatomaceous earth mixed with water and sprayed it onto the vines. We used 20 grams per litre of water, 400 litres per hectare."

Three sprays were undertaken a week apart, from October 30 until November 14. Sprays of DE and kaolin, and a spray of just kaolin were also used. What was interesting was the different affects on two varieties – Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. The results in each block were compared with a control, where nothing was sprayed, Chang said.

"When sprayed onto Chardonnay, there was 23 percent less damage when using DE, K-DE and Kaolin when compared with the control.

"On Pinot Noir there was 46 percent less damage. This suggests there is a varietal effect affecting vine consumption by the beetles."

He followed this up by comparing the severity of damage created by beetles in two blocks, with just a roadway between them. One side of the road had Sauvignon Blanc vines, the other side had Pinot Noir.

"So they had the same soil type and the same exposure. But there was a clear difference between the damage in the two varieties, with Pinot Noir suffering more."

Chang's research will continue this season. He said there are a number of avenues he wants to follow up on.

"What we want to find more about is the feeding disruption. We would like to understand the female behaviors better. Do they land first on the plant and then, using pheromones attract the males? If that is the case, we can try to modify that.

"In addition they feed only after they mate. So if we can disrupt the mating, maybe we can stop the feeding. We want to combine the mussel shells with feeding deterrents in one treatment. We had a 60 percent reduction in damage with shells and about 40 percent with deterrents. If we combine the two, we might have an even better effect.

"We will also look at cover crops and Miscanthus x giganteus, which is a plant that can grow four metres in two years. If we place these plants at the edges of the vineyards, maybe it would act as a barrier and stop the beetles' flying pathways."

In the meantime we are heading into the season when beetles will be out in force. There is some thought that covering the outside vines with netting can be useful in deterring the beetles. Also cultivating between the rows, which brings the larvae to the surface as fodder for birds is another useful tip. ν

Chang's research has been supported by Callaghan Innovation, Kono Beverages, Lincoln University and Bio Protection Research Centre.