They will then carry on with the same drenching programmes that proved successful on their property in the past. I believe that most farmers will either have a regular pattern of drenching every four, six or eight weeks, depending on the degree of worm challenge – which will vary greatly throughout the country. Or they will only drench lambs when needed or at convenient times when they are yarded.

Farmers have received advice from scientists, vets and Beef+Lamb NZ Wormwise personnel, who organise workshops throughout the country.

Much of this advice varies greatly from drenching every four weeks to prevent worms from maturing, thus preventing them from reaching their egg shedding stage; to leaving the best lambs undrenched to ensure the survival of worms that have no resistance to drench so they can mate with their most resistant mates, thus slowing down the progress towards drench resistance – the “refugia” concept. All this varying advice farmers would find confusing.

Since effective chemical drenches were developed 70 years ago, farmers have been able to control worm challenges, ensuring better growth rates and preventing most deaths. This was a great boon that provided greater profitability.

With the benefit of hindsight, I believe this success led farmers to over-drenching, thus shortening the effectiveness of each drench that has led to drench resistance.

However, there are always negatives to all human discoveries: The boom in the plastic industry, for example. So too with chemical drenches.

Three adverse effects of chemical drenches come to mind that are seldom mentioned.

The drug companies state that their product will kill 99.9% of worms. With genetic variation, some animals will have more or less resistance to worms. When I first began breeding for worm resistance, I found a fivefold difference in the average worm egg count of the progeny of 12 stud sires.

This assured me that progress could be made breeding for worm resistance.

These efficient drenches ensured good growth rates and survival of the most worm-susceptible sheep, many of which would be selected in breeding flocks and collectively in our national flock. The same applied to the rams we bought.

Thus, every generation would be slightly more susceptible to worm challenges. Beef+Lamb NZ’s SIL people tracked this trend from 1990 to 2006 in a graph, which indicated about a 6% decline in worm resistance over that period.

I have no information on this decline over the whole 70 year period but believe it would be considerable. As the immune system is the only force that controls diseases and internal parasites, a conclusion can be drawn that the immune system has been bred to become less effective over the past 70 years through the use of chemical drenches.

The second negative impact of drenching is related to the first. It involves the 0.01% of worms that survive drenching. Thus only 12 in 1,000 of surviving worms is never mentioned.

These resistant worms mate and some but not many with the principle of genetic variation will be more resistant than their parent. So, we have inadvertently set in motion the best imagined programme to breed super worms.

The third negative of drenching is that worms and challenges from disease are required to challenge the immune system to set it in motion so to speak.

Keeping lambs free of worms by frequent drenching will retard immune development. The same applies to diseases. Many years ago, when discussing this with Dr Jon Hickford of Lincoln, when his children were small, he said he liked his children to play in the dirt “at least twice weekly” – obviously to ensure the development of a strong, lifelong immune system.

How does all this affect our thinking on drenching programmes?

I would suggest two different drenching programmes: one for the wether lambs and others destined for the works; and a different strategy for the ewe lambs from which “the keepers” are selected.

For the works lambs, drench when required to ensure maximum growth to ensure early departure. But remember the meatbred lambs are far more worm susceptible and are where Haemonchus is present.

It would pay to run them separately and keep them closely monitored, as even prime lambs can die very quickly.

For the ewe lambs, minimal drenching is recommended. In warmer areas, an early drench may be required to control tapeworm which can cause severe scouring and flystrike.

Otherwise, I would not advocate early drenching, even at weaning, because the worm challenge is low and the immune system can control it.

By not drenching the better lambs, the worms they carry will ensure immunity will continue to develop. By all means drench the tail end and sickly lambs, as they will benefit and grow.

In my area, worm levels will continue to increase through December into early January.

Monitoring worm levels is cheap and easy; simply put a mob of lambs together in the corner of the paddock for five minutes.

You need to collect 10 to 15 dung samples. Thoroughly mix them, then take one sample, the equivalent of six dung marbles, then get your vet to send them off to be counted.

If the average is less than 1,000 I would only drench any that look lethargic or sickly. Mark any drenched lambs and preferably run them separately. When I adopted a no drench policy for my ram lambs, the average faecal egg count (FEC) would average 3,500 to 4,500 with a few over 20,000.

This high count is typical when Haemonchus – the Barbers Pole worm – is the dominant species, because this worm sheds huge numbers of eggs every day – scientists have estimated up to 10,000.

|

|---|

|

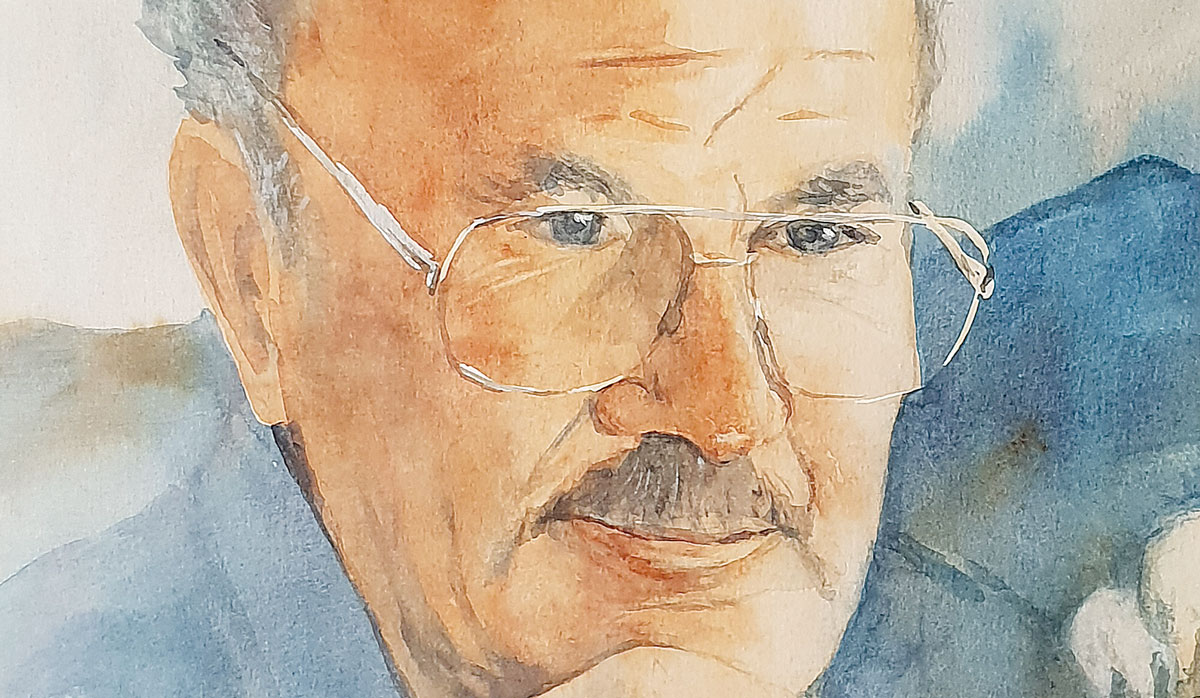

Long-time Northland ram breeder Gordon Levet has been breeding worm resistant rams for several years. |

The build-up of the worm challenge will be later and slower in cooler and higher altitude regions.

From mid-January on, try only drenching those that show signs of parasitism and mark them. By mid-April the lambs should have immunity that is well-developed and the worm challenge will start to decline.

Where Haemonchus is the dominant species, more observation will be needed and possibly the whole mob may need drenching. In selecting ewe replacements, take into consideration those that have fewer or no drenching. This would be a tiny step in the mile long direction towards worm resistance.

To sum up, worms and other diseases are nature’s way of building an effective immune system. By removing the worms by drenching, we will help the lambs but interrupt immune development.

So, drench ewe lambs as little as possible, especially early on. Good stockmen will know instinctively when lambs need a drench.

These are management practices that can reduce worms and disease challenges and I hope to cover these issues in later articles.

Gordon Levet is a longtime ram breeder from Northland