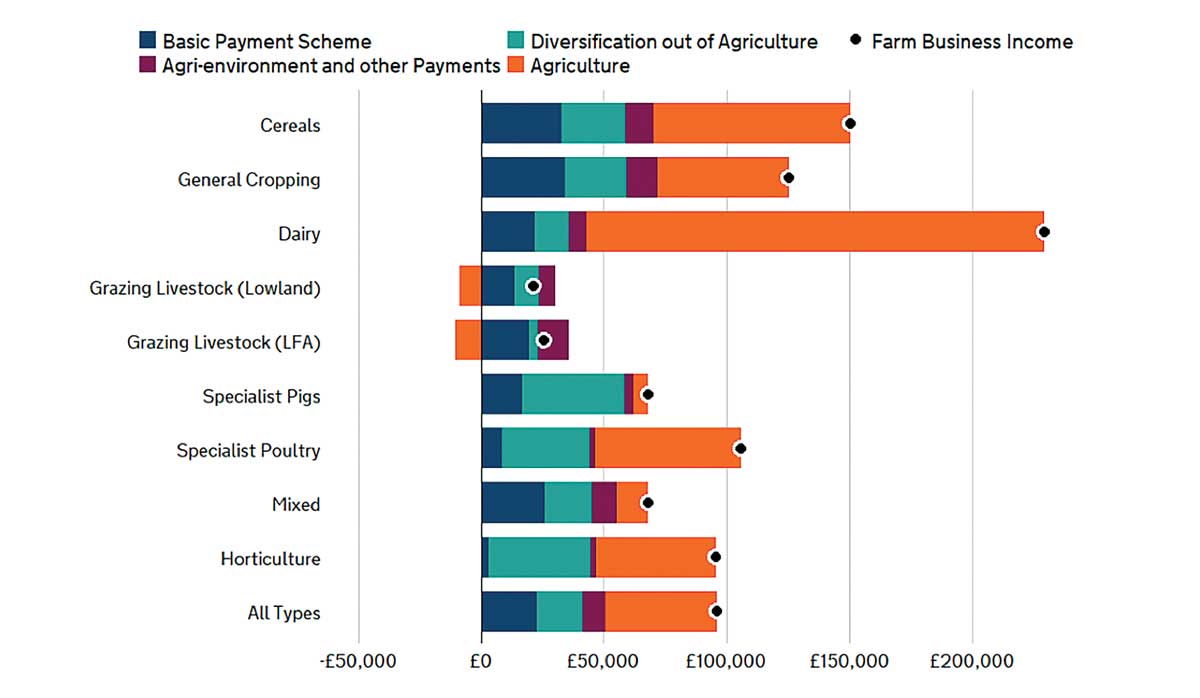

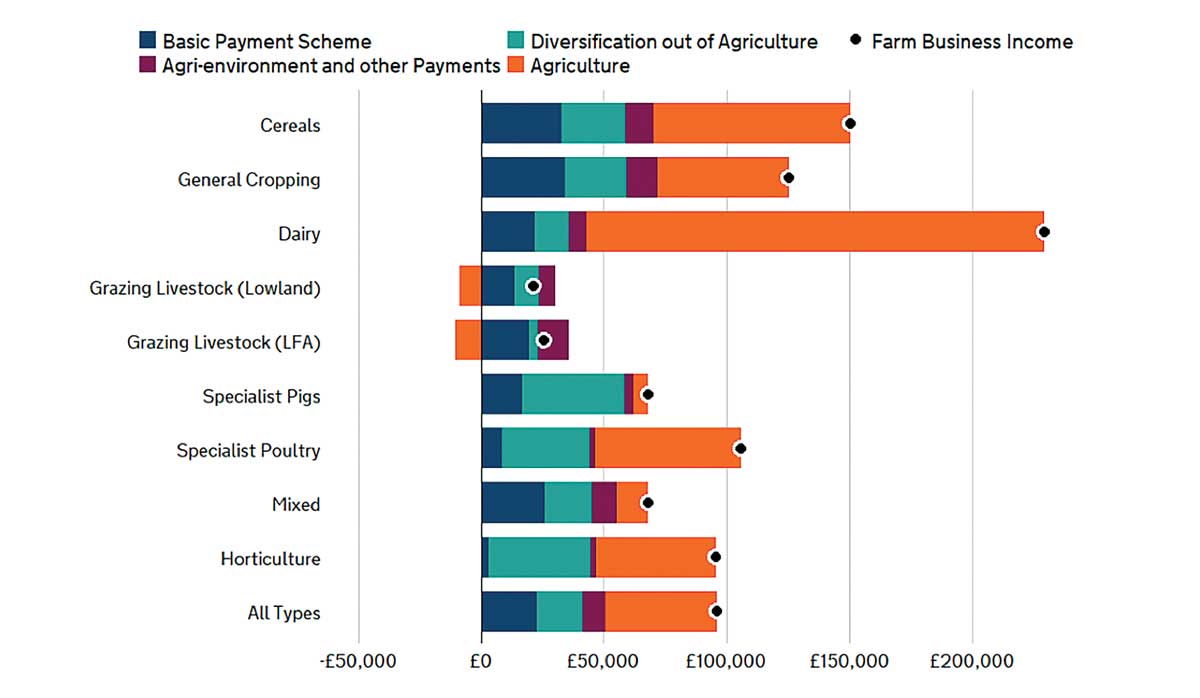

OPINION: In March this year, Defra (the UK Government Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) published the national statistics for farm business income. The figures indicate that most farms make more money from support mechanisms and ‘diversification out of agriculture’ than they do from food production.

For livestock grazing, the agricultural part of the equation is negative – it is the basic payment scheme and the ‘Agrienvironment and other payments’ that keep the households afloat.

No wonder, then, that the British farmers are wary about free trade deals with other countries. No wonder that they are extremely concerned about what the new Labour Government will do about the subsidies.

The UK is not in the European common agricultural policy and since Brexit, farmers no longer receive payments directly linked to how much land they manage. Rishi Sunak’s government had committed to spending £2.4bn a year in England on payments for farmers. These were mostly linked to environmental improvements made on their land and replaced area-based payments. Historically, farmers feel that they have tended to do better under Labour than Conservative governments. This time, they aren’t holding their breath.

Analysis of the political manifestos shows why.

Labour, unlike the other two main parties (Conservative and Liberal Democrats) did not have a clear commitment to a budget that underpins sustainable domestic food production, delivers for the environment and supports all land tenures. Nor did they appear to have any angle on domestic food security and proportion of food grown in the UK.

In contrast, New Zealand does not have support payments (unless in drought or flood) and focuses more on the amount of food exported than imported. Domestic food security is a moot point. We rate relatively highly in the global food security index (15th of 113 countries and score 100% in having food safety net programmes, as does UK), but media portray a different story.

UK Labour also didn’t have a plan to invest in agricultural technology and innovation centres, whereas New Zealand’s Government did create and provide co-funding for the initiative now called AgriZero.

In both countries, farmers are worried about economic viability.

farmers can point to maintenance of iconic countryside and biodiversity as part of their work (in the UK farmers have been paid for maintenance whereas in New Zealand it is simply what we do).

In both countries people are complaining about escalation of food prices.

This is the dilemma for governments – in the UK the balance is between payments to farmers and keeping taxes to societies down, whereas in NZ it is the licence to operate versus allowing efficiencies in agriculture (preferably while reducing non-productive paperwork).

In both countries, people in power are trying to identify the best path forward for their areas of activity. In the UK there is a proliferation of advisory groups, including a website dedicated to showing how they all interact. In New Zealand the Interdepartmental Executive Board for Climate Change ensure information flow between ministries.

|

|---|

|

Cost Centre breakdown for Farm Business Income by farm type, 2022-23. DEFRA March 2024

|

Early indications are that progress is being made. The Second Emissions Reduction Plan, currently out for consultation, includes the statement in the Technical Annex that “Production is assumed not to be affected by agricultural emissions pricing”.

This is, at last, an acknowledgement of the Paris Agreement and ‘countries should do everything they can to reduce greenhouse gases without compromising food production’.

It indicates a concern for global food availability, not just domestic food security.

With our excellent GHG credentials for high quality protein production (meat and milk), the global concern could be part of our marketing advantage.

Time will tell, as it will in the UK. In the meantime, farmers in both countries need a voice in government’s ear. NFU, Federated Farmers, industry, levy bodies – all play a part and do what no farmer can do alone. All are supporting farmers in the goal of economic viability. Global food security depends upon success.

Dr Jacqueline Rowarth, Adjunct Professor Lincoln University, is a director on the board of governance of DairyNZ, Ravensdown and Deer Industry New Zealand. She remains in touch with farmers in the UK, after emigrating to New Zealand.