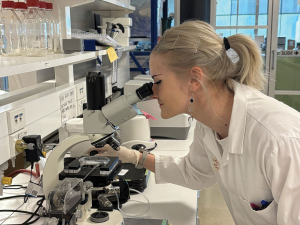

Auckland University master's student Rebecca Strange presented her research into Saccharomyces cerevisiae at the New Zealand Wine Centre Scientific Research Conference in Blenheim in June, and was named runner up in the Best Student Award. She shares some insights into her thesis.

Please explain your study

My master's research aimed to hybridise Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the yeast commonly used for New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc fermentation, with the cold-tolerant Saccharomyces uvarum, to create a strain that maintains strong fermentation performance even at the low temperature typical of this style.

What drew you to this research topic?

I have always been excited by genetics and biotechnology and, of course, wine. The idea of combining traits from two different species through hybridisation to create a yeast with the best of both worlds scratches a very specific itch in my brain.

Why ferment Sauvignon Blanc at lower temperatures?

Fermenting Sauvignon at 10 to 15C enhances the classic New Zealand Sauv character. The cold temperature helps preserve delicate aromatics, such as thiols, that contribute to the fresh and fruity aromas typical of the variety and style.

What happens to Saccharomyces cerevisiae in those lower temperatures?

Saccharomyces cerevisiae works best at warmer temperatures of about 20 to 30C. It tends to slow down in cooler temperatures such as 12C, taking longer to start fermenting and producing a lower maximum fermentation rate. This causes a few problems. First, slower fermentation means the process takes longer, which can be more expensive for winemakers because valuable tank space is tied up. Second, if Saccharomyces cerevisiae can't dominate the fermentation, other unwanted microbes might grow, increasing the risk of spoilage.

Is there a better yeast choice?

Saccharomyces uvarum is a less domesticated yeast species commonly used in cider and lager fermentations, which take place at colder temperatures. Winemakers may notice Saccharomyces uvarum in cool fermentation, where it can initially outcompete other yeasts like Saccharomyces cerevisiae, sometimes producing undesirable aromas. However, Saccharomyces uvarum has a lower alcohol tolerance, which reduces its ability perform at ethanol levels increase throughout fermentation. A hybrid between the two, uniting the best qualities of each species, could deliver superior fermentation performance in the cold!

What's next for your research?

Unfortunately, I was unable to obtain a hybrid within the limited timeframe of my master's thesis. However, I am currently preparing a publication based on my thesis findings, focusing on the genomes of New Zealand Saccharomyces uvarum populations and their cold tolerance traits. I am actively exploring PhD opportunities to continue yeast-related wine research. I am deeply passionate about yeast and believe their potential in winemaking is vast. I hope to contribute to advancing yeast biology and encourage greater focus on the yeast side of winemaking in future studies.

Read More: