Claims that farmers are polluters of waterways and aquifers and 'don't care' still ring out from environmental groups and individuals. The phrase 'dirty dairying' continues to surface from time to time. But as reporter Peter Burke points out, quite the opposite is the case. He says, quietly and behind the scenes, farmers are embracing new ideas and technologies to make their farms sustainable, resilient, environmentally friendly and profitable.

A good example of the good things that are happening is near the small rural settlement of Kimbolton in the Manawatu.

It’s here that a significant research project is taking place to reduce the amount of nitrogen on a farm going into a local steam - Haynes Creek - and into other connecting waterways.

Scientists from Massey University School of Agriculture and Environment, local farmers and the Manawatu River Collective have been working collaboratively on a pilot demonstration of a woodchip bioreactor, project which is already showing that nitrogen levels can be significantly reduced in drain flows from farming landscapes.

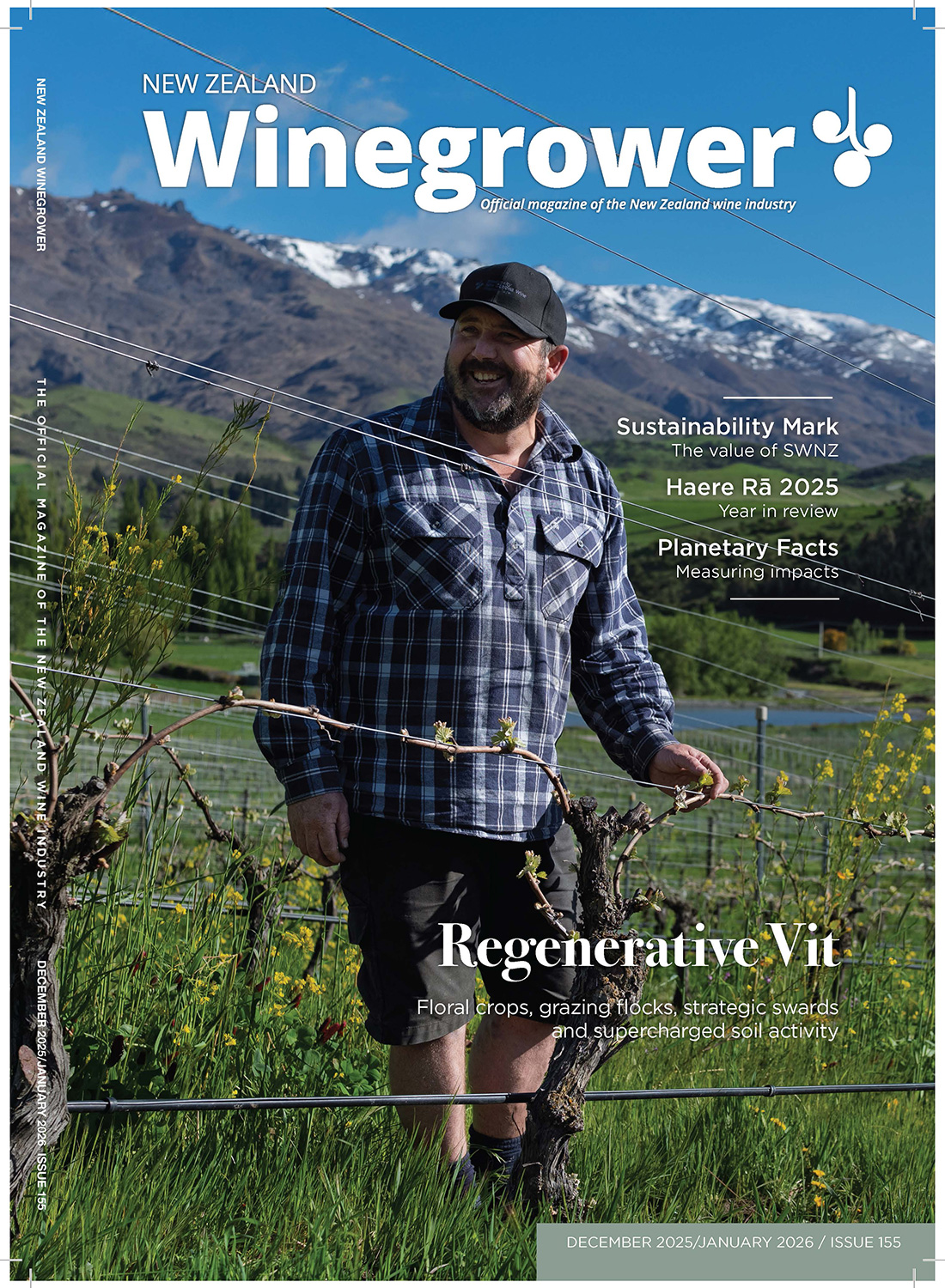

A woodchip bioreactor has been built on the 300ha farm of Dr Margaret and Richard Brown on which they run sheep and cattle but also have extensive cropping, producing winter and summer wheat, peas, barley and even Brussel sprouts. The soil on the land is heavy silt clay loam and early testing showed that nitrate levels in one of the drains on the property was high, and there are number of drains on the property which flow into the local stream, known as Haynes Creek. The Browns belong to the Haynes Creek Catchment group – one of 15 such groups in the greater Manawatu region – as part of the Manawatu River Catchment Collective.

Margaret works off farm as a social scientist with AgResearch and admits to having an abiding interest in environmental science. It was at a meeting of the Haynes Creek Catchment group, which has a membership of about 55 landowners, that the idea of installing a wood chip bioreactor on one of the farms in the group was mooted as part of the Catchment Solutions project.

“We were one of four farmers who put their hands up and, in the end, we were selected for the pilot trial in Haynes Creek,” says Margaret Brown.

She says they had been sampling water on their farm for about eight years and knew that they, like others in their catchment, had similar problems with high elevated nitrate levels in drain waters and were looking for ways to mitigate this.

“At a personal level we were keen to find out what could be done, but we were also keen to share the findings with other farmers,” she says.

The site chosen for the woodchip bioreactor was a 22ha block of land, or mini catchment or small gully where the land has been tile drained and flows into a small drain, which ultimately flows into Haynes Creek.

Throughout this process, Massey University’s environmental hydrologist, Professor Ranvir Singh, and Manawatu River Catchment Collective co-ordinator, Fiona Burke were deeply involved.

Fiona Burke says her objective was to get farmers involved and have ownership of the project. She says now a lot of regulations are coming in and there appears to be few options available to fix some of their problems.

The Bioreactor

Professor Ranvir Singh says each site is different and a huge amount of co-learnings and work went into planning the project on the Brown’s property.

From the gully there is a constant flow of water into a drain and in the middle of this has been built the woodchip bioreactor, complete with an array of sensors to measure the level of nitrate in the water before it goes though the wood chips and when it comes out the other end. The woodchips, which contain carbon, denitrify the water and it takes about 16 hours for the water to go from one end of the bioreactor to the other.

As well as fencing off the bioreactor, the Browns, in conjunction with the catchment collective, have carried out extensive riparian planting further down the drain to improve water quality and biodiversity.

The Browns did most of the earthworks associated with constructing the bioreactor. They also run a contracting business and had the necessary heavy machinery. A huge hole was dug, into which the wood chips were placed.

According to Fiona Burke, the actual woodchips are quite expensive as they must be cut to a specific size and have the bark removed. In this trial the area around the bioreactor has been fenced off to protect the measuring instruments, but in normal circumstances it would just be a part of the paddock and stock could graze on it. Professor Singh says the bioreactor contains about 300 cubic metres of wood chips.

“We have been monitoring this site for two years; less last year because it was a very dry season. But this year we have got good data, and we have been seeing a huge reduction in the nitrate outflow. But we are still completing our analysis and will build up good data sets that we will be able to share with farmers,” he says.

He says the challenge is that this was only a three-year project and funding will have run out next year. He says Massey is hoping that the catchment group can get additional funding so that performance monitoring and lessons from the trial can continue for longer.

He believes the trial has been successful so far and says a very positive outcome has been collaborating with farmers and ensuring that what is being done is practical.

Is It Cost-Effective?

While the trial so far has produced excellent results in terms of reducing nitrate levels, this must be weighed against the cost of installing a woodchip bioreactor, which in this case is about $10,000 to service just 22 hectares.

Margaret Brown says the cost is high and may not be practical. However, she says they are waiting to get more data from the trial and also see what the new regulations may look like – and that will guide them in terms of future options.

Fiona Burke says regardless of the final outcome, the bioreactor trial at Haynes Creek has produced many benefits. She is the co-ordinator for 15 catchment groups with a membership of nearly 500 farmers in the Manawatu. She sets up meetings, organises field days and brings in experts to meet with farmers and exchange ideas.

|

|---|

|

A woodchip bioreactor has been built on the 300ha farm of Dr Margaret and Richard Brown.

|

Burke says her role is to run some social functions to bring together farmers and their families, many of whom feel quite isolated and have few opportunities to share knowledge and problems and socialise with each other.

“I think this project has been a learning curve from both the farmers’ side and Massey. The scientists have learned to slow down and explain what they are doing in ways that farmers can understand it. The good bit is they have listened to farmers and designed things that work in their environment,” she says.

She says farmers don’t want to be lectured to, they just want to know what’s wrong and what to do.

One such farmer is Mark Burke, neighbour of the Browns, and who is long time member of the Haynes Creek Catchment group. He’s been measuring water quality on his farm for several years and using Overseer, so knows his numbers.

He says he’s been following the trial closely and believes the use of a woodchip bioreactor could be of potential benefit to him in the future. Mark Burke says he enjoys being part of the catchment group because it gives him the opportunity to meet with farmer colleagues and share knowledge on how to improve the environment.

“My personal view is I want my farm to be sustainable, resilient, tick the environment boxes and also I want to make money,” he says.

For more information visit https://catchmentsolutions. co.nz/virtual-tours/